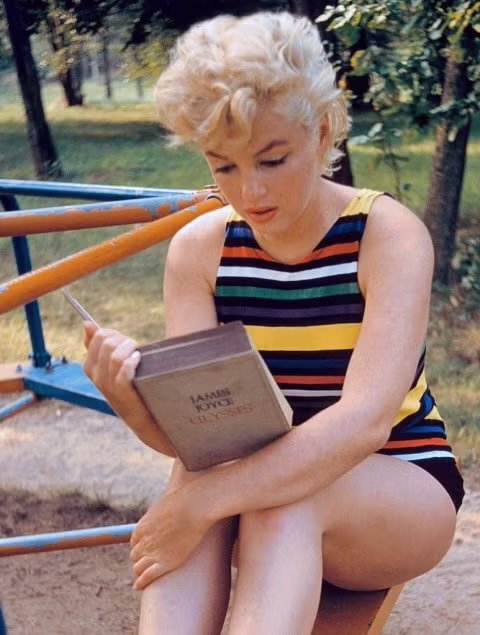

Jackie or Marilyn?

Why must we still be stuck choosing between being hot or being taken seriously?

Marilyn Monroe reading James Joyce's Ulysses, proof that beauty and brains are not mutually exclusive. Courtesy of Eve Arnoid. Available via ELLE. © All rights belong to their respective owners. No copyright infringement intended.

The Jackie-Marilyn dilemma is one of those cultural frameworks that sounds outdated but still quietly shapes how women are perceived, and how they’re expected to behave. Coined from the infamous triangle between Marilyn Monroe, John F. Kennedy, and his wife Jackie Kennedy, the idea boils down to this: women can either be respected or desired, never both.

You’re either a “Jackie”: brunette, elegant, intelligent, refined. Or a “Marilyn”: blonde, sexy, frivolous, and promiscuous. The assumption being, of course, that those things are mutually exclusive. That if you're taken seriously, you can't also be alluring. And if you're desired, you can’t possibly be smart or respectable.

The dichotomy isn’t new. “Blondes vs. brunettes” has been a pop culture trope forever, long before Monroe and Kennedy were household names. But it was this specific dynamic, with all the drama of politics, infidelity, and iconic American femininity, that solidified the fantasy. Jackie represented the wife, the mother, the First Lady. Marilyn was the mistress, the fantasy, the downfall.

But here's the thing: Marilyn wasn't sexy because she was blonde. And Jackie wasn't dignified because she was brunette. These weren't inherent traits, they were media constructions. Archetypes built and sustained by the same narratives that keep us asking, even now: are you a Jackie or a Marilyn? A Charlotte or a Samantha?

This lens lingers because it’s deeply woven into how femininity gets processed, especially when it makes people feel uncertain or out of control. When a woman doesn’t immediately fit a familiar script, people rush to categorize her, reaching for whichever archetype feels safer.

These categories get assigned fast and stick hard. Suddenly, a single trait, the way she dresses, speaks, moves, becomes the whole story. And even if she tries to shift or expand, the narrative resists.

What started with Jackie and Marilyn shows up now in all kinds of lazy opposites: elegant vs. wild, composed vs. chaotic, clever vs. fun. None of it has anything to do with hair color. It's about how women are boxed in based on how they present, and how they're consumed. The labels change, but the instinct stays the same: keep women in their place by making sure they only get to be one thing at a time.

Jackie Kennedy was always described as graceful, cerebral, soft-spoken, classy. Not because of her dark hair, but because that was the narrative built around her. Marilyn, on the other hand, was constructed as the opposite, as lesser. Her sensuality automatically disqualified her from being serious, despite her intelligence, wit, and evident business savvy.

Don’t get me wrong, this isn’t just about pop culture history. It still affects how women navigate workspaces, relationships, and even friendships. Women who embrace makeup, heels, or hyper-femininity are often viewed as “less than” by default. Those who dress down or play it cool might be respected, but not necessarily desired. The myth still thrives.

Freud, problematic as he was, coined a similar idea in psychology: the Madonna-Whore Complex. According to him, some men psychologically split women into two categories: Madonnas (pure, virtuous, maternal) and whores (sexual, impure, threatening). Sound familiar? Studies today show men who hold these binary views of women are more likely to be sexist and also struggle with intimacy in their relationships.

So what does this mean for women today? It means the pressure to pick a lane, Jackie or Marilyn, saint or slut, is still alive, still oppressive, and still false.

Because we’re neither. We’re both. We’re something else entirely.