The Perennial Gothic

Gen-Z channels gothic romanticism through baroque textures, corseted silhouettes, and shadow-toned palettes, composing an aesthetic vernacular rooted in Victorian mourning, subversive femininity, and the haunted architecture of literary memory.

Bella Hadid wears custom Dilara Findikoglu for the 2022 Met Gala after-party, a translucent corseted composition structured with anatomical boning, cruciform lacing, and sheer black mesh that evokes Victorian mourning dress, ecclesiastical fetishwear, and post-rave sanctity, positioning the body as both sacred object and site of aesthetic resistance. © All rights belong to their respective owners. No copyright infringement intended.

Jonathan Anderson’s New Look for Dior Homme conjured aristocratic nonchalance: the thrill of today’s youth stumbling upon their great-great-grandfather’s frock coats in a dust-covered trunk at the summer chateau. An 18th-century moiré waistcoat thrown over jeans and sneakers felt less like costume, more like reclamation. This grunge-tinged remix of antique menswear is fuelling a wider resurgence of goth in fashion — a style steeped in the bleakness of Victorian England and the sombre defiance of late 18th-century feminist literature. Anderson’s indirect nod to those roots came with a revamped Book Tote stamped with the title of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, slung over the shoulder with the kind of devil-may-care attitude that punctured the stiff air of the cavernous show space at Les Invalides.

Dior’s latest menswear collection isn’t goth in the literal sense, but it carries the phantasmagoric air of dark romance, a mood rooted in gothic fiction and historical silhouettes, now recharged by Gen-Z as a response to socio-political unrest. For a generation coming of age under the pressures of climate collapse and an accelerating technological revolution, dressing like a ghost feels oddly appropriate — a way to capture the feeling of invisibility.

The gothic aesthetic haunts runways through 18th-century couture techniques: Edwardian puffed sleeves, Elizabethan corsets, Victorian crinolines. On the streets, it’s more accessible through ripped fishnets, distressed fabrics, and heavy chains, all immortalised on TikTok under hashtags like #RomanticGoth and #GothicGlam.

Designers from Bora Aksu to Thom Browne to Dilara Fındıkoğlu have channeled this spirit, blending period drama with subversion. Dilara’s vampiric Fall 2025 show, for instance, staged a “divine feminine mutiny” that offered goth girls everywhere a new fantasy to inhabit.

And then there’s Gabbriette — Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride come to life, billed as the Sky Ferreira of the TikTok era. Not so much anointed as imposed, she’s become the industry’s de facto goth-lite girl: perfectly packaged to peddle eyeshadow and indie sleaze to the merciless algorithm.

LEFT: Riding the wave of Netflix’s dark academia hit Wednesday, London-based Turkish designer Bora Aksu infused his Fall 2023 collection with gothic elements, as seen in this brooding black velvet minidress detailed with embroidered lace. RIGHT: Two years after Bora Aksu’s show, fellow Turkish Londoner Dilara Fındıkoğlu unveiled Venus In Chaos, a collection of otherworldly, ethereal gothic looks — like this black mesh dress, subtly structured with corset boning to accentuate the figure. Images sourced via Vogue Runway © All rights belong to their respective owners. No copyright infringement intended.

The Gothic novel reached its vogue moment in the late 18th century, popularised by writers like Ann Radcliffe. In The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), Radcliffe weaves the atmospheric visuals of medieval architecture with the psychological torment of a heroine trapped by patriarchal systems — a dynamic that still resonates more than two centuries later. The Female Gothic wasn’t just about ghouls and gloom; it was coded to protest institutional and domestic repression.

Today, the genre surfaces in cinema, though not always faithfully. Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things (2023) reimagines Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) with a female lead, but the result feels like a gender-swapped downgrade. Where Shelley’s original buried feminist critique within a male-dominated narrative, Lanthimos gives us a heroine whose “awakening” leads her to a brothel, the tired endpoint of many male fantasies masquerading as liberation. Here’s hoping Maggie Gyllenhaal’s upcoming take on the classic fares better.

Gothic fashion draws heavily from Victorian mourning codes, when widows were mandated to wear black crepe for at least two years to signal grief and self-restraint. But today’s update on the macabre uniform — velvet, lace, silk — no longer whispers repression. For Gen-Z, wearing black isn’t about mourning a partner, but defying an institution.

When The Batcave opened in London’s Soho district in 1982, it became ground zero for goth as the first club of its kind. Born out of post-punk’s raw energy, it carved out a space for misfits to gather and experiment with theatrical make-up, tousled hair, and the fetishistic uniform of leather and latex. Image sourced via The Standard courtesy of Derek Ridgers © All rights belong to their respective owners. No copyright infringement intended.

Before this decade’s third-wave Gothicism, the subculture first emerged in early 1980s Britain, rising from punk’s ashes in post-industrial satellite towns where disenchanted youth languished in the shadows of the capital; yet societal neglect also haunted London itself, most notably in Soho, where urban goths found refuge at The Batcave, an underground club for card-carrying members of the subculture. Those who passed through its coffin-shaped doors experienced arthouse films, cabarets, and live music that deepened their bond with darkness.

Today’s descendants of that gothic renaissance engage with the trend on a different level — politically and intellectually. Patriarchal power hierarchies restricting upward mobility reached a boiling point a decade ago with the #MeToo movement, exposing the humiliations women endured to progress in male-dominated industries.

These same abuses, aimed at invalidating female autonomy, were integral themes in Female Gothic texts now rediscovered by Gen-Z through BookTok, an outspoken TikTok community centred on a shared love of literature. Far from niche, the trend caught the attention of luxury brands — last year, Miu Miu staged a Summer Reads pop-up in Covent Garden celebrating female authors who give voice to the perennial disillusionment of young women, over a third of whom live with mental health conditions, according to the NHS.

Since the pandemic, mental health struggles have surged as mortality returned to the foreground and the internet generation embraced the morbid paranoia that once plagued their Victorian ancestors. The macabre undertones of lockdowns and isolation added weight to the gothic revival, especially for those still feeling COVID’s lingering effects amid a crushing cost-of-living crisis. As capitalism strains under the pressure, Gen-Z increasingly turns toward socialism — evidenced by the debt-ridden graduates who formed the core electorate of New York City’s Democratic Socialist mayoral candidate, many of whom now struggle to launch the very careers that higher education promised them.

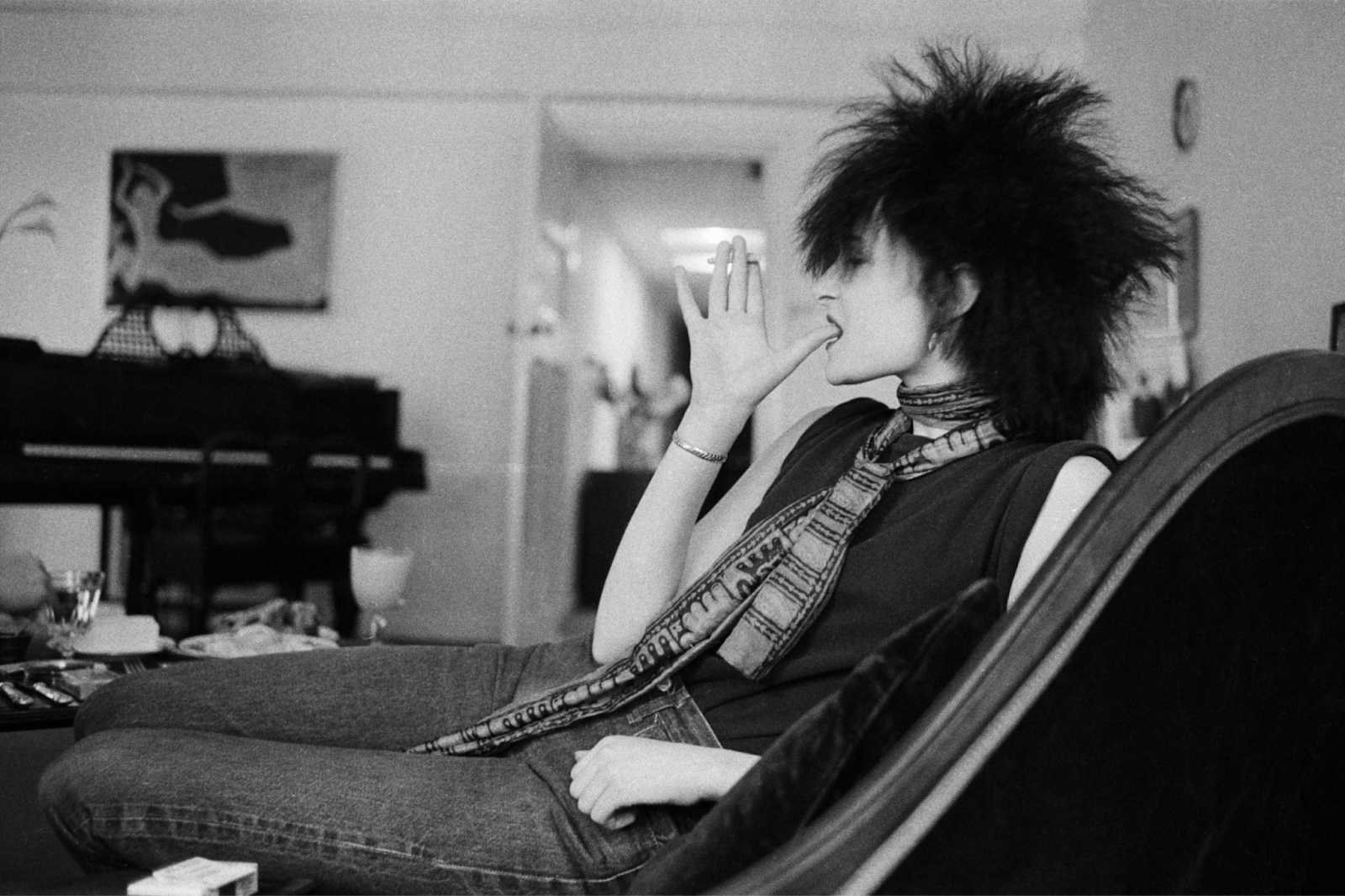

Where society represses, fashion expresses. It’s why Siouxsie Sioux’s untamed hair or Fiona Apple’s soulful shrieks remain seared into our collective memory — because the arts elicit strength from sadness. Music and fashion bridge the gap between the ideal and the real, transforming private anguish into something communal. They remind us of the connective tissue between our individual alienation.

The injustice of limiting self-discovery, especially for teenage girls navigating identity in a chaotic world, has fuelled female existentialism long before Ann Radcliffe ever put pen to paper. Today, corsetry is back not just for aesthetics, but for symbolism. It speaks to the long history of moulding the female form to fit male ideals, a language the fashion industry still struggles to unlearn. Just compare how few women hold creative directorships compared to their male counterparts.

Personally, I’d have welcomed Dilara Fındıkoğlu’s exploration of unearthly femininity at Alexander McQueen — a match made in heaven, or more aptly, hell — over Seán McGirr’s amateurism.

Siouxsie Sioux emerged as a defining countercultural force in late ’70s Britain, fusing punk with a dark, theatrical edge that would crown her the “Godmother of Goth.” Image sourced via Snap Galleries courtesy of Michael Putland © All rights belong to their respective owners. No copyright infringement intended.

Goth’s tough exterior of safety pins and opaque blacks only seeks to protect a fragile core, the kind of femininity that’s been prodded and punished since the dawn of human consciousness. This cultural shift — the perennial gothic — keeps a moonlit glow on the struggle, casting light through an otherwise impenetrable night of apathy. Let every corset, every veil, stand as a visual reminder of captive femininity… and the quiet refusal to let it stay that way.